Southwest Climate Outlook El Niño Tracker - November 2018

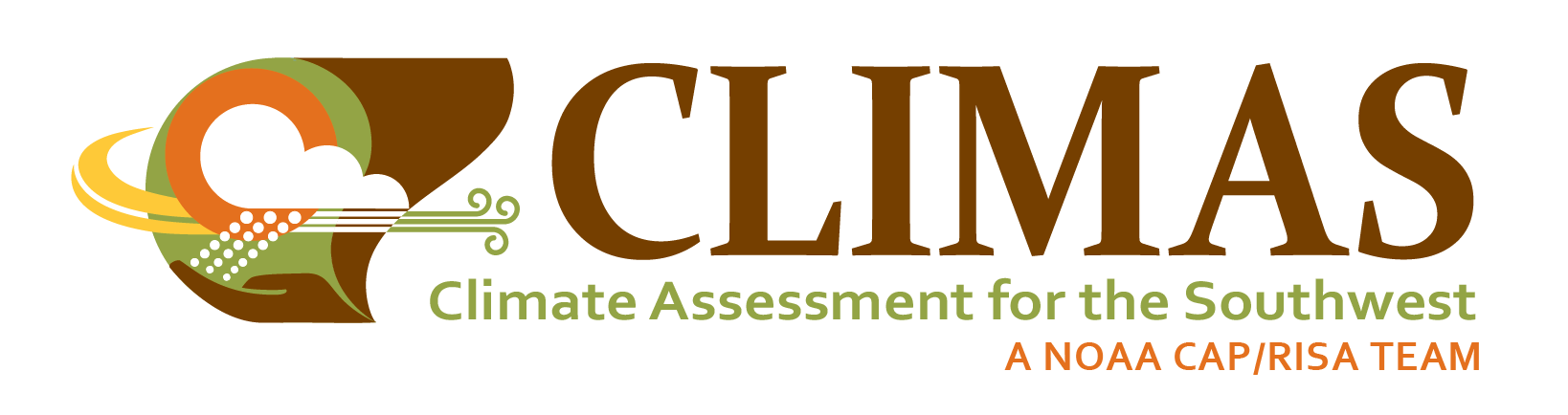

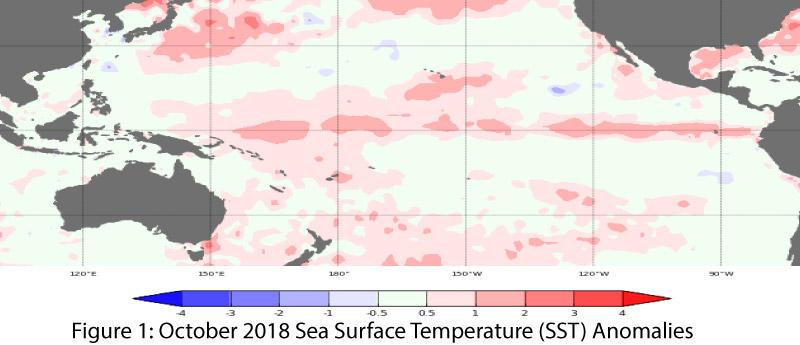

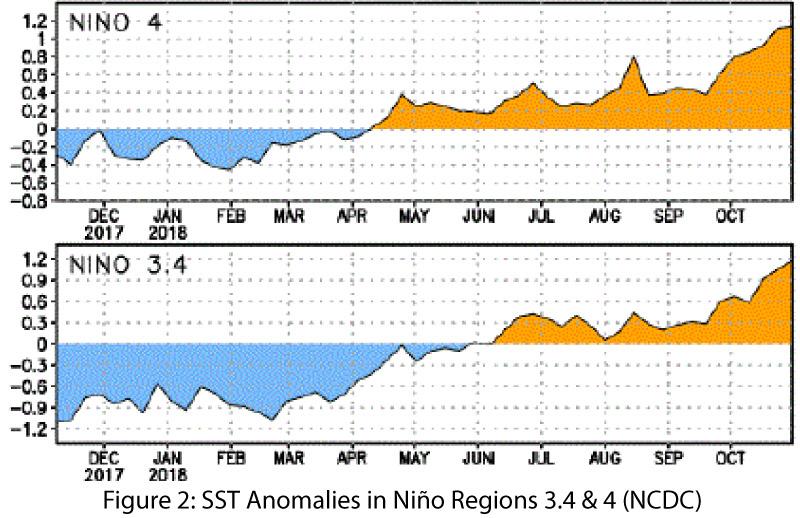

Not quite El Niño? Widespread areas of above-average sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) now exist in the equatorial Pacific (Figs. 1-2), but atmospheric conditions have lagged behind. Most forecasts and outlooks, while still bullish on the emergence of an El Niño in 2018, identified current conditions as ENSO-neutral, but see an imminent shift in atmospheric circulations more characteristic of an an El Niño event. On Nov. 7, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology noted persistent above-average oceanic temperatures, but saw the continued presence of atmospheric conditions much closer to normal. The agency noted that coupling between oceanic and atmospheric conditions “is critical in any El Niño developing and becoming self-sustaining.” It maintained its ENSO Outlook at an “El Niño Alert,” with a 70-percent chance of its formation in 2018. On Nov. 8, the NOAA Climate Prediction Center (CPC) continued its El Niño watch, identifying neutral conditions at present and an 80-percent chance of an El Niño event developing this winter, and a 55- to 60-percent chance of it lasting through spring. CPC also noted the lack of oceanic/atmospheric coupling as hindering the progression of an El Niño event in an otherwise much-warmer-than-average ocean. On Nov. 8, the International Research Institute (IRI) issued an ENSO Quick Look that also reflected the warmer-than-average oceanic temperatures and the lagging atmospheric conditions, and maintained a greater-than-80-percent chance of an El Niño event by the end of 2018 (Fig. 3). Breaking from the other agencies, on Nov. 9, the Japanese Meteorological Agency (JMA) did identify the presence of El Niño conditions in the equatorial Pacific, with a 70-percent chance of these conditions lasting through spring 2019. JMA declared the El Niño despite the absence of atmospheric conditions consistent with such an event, stating that the lagging onset and resulting conditions are “common features of past El Niño events.” The North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) points toward a weak-to-moderate El Niño by the end of the year (Fig. 4).

Summary: Equatorial SSTs have been rising and would appear to indicate the onset of an El Niño event except that the atmospheric patterns remain ENSO-neutral. Most outlooks are not particularly concerned about the current lack of oceanic/atmospheric coupling and expect that to occur by year’s end—in fact JMA considers the El Niño to have already begun. Further, most forecasts call for this El Niño event to last through spring. Cool-season precipitation totals (Oct – March) in the Southwest during previous El Niño events reveal considerable variability under weak events, including some drier-than-average seasonal totals. However, under moderate-intensity events, drier-than-average cool seasons have been rare, and it is not difficult to understand why there is eager anticipation for anything that might increase our chances of more winter rain.

Online Resources

- Figure 1 - Australian Bureau of Meteorology - bom.gov.au/climate/enso

- Figure 2 - NOAA - Climate Prediction Center - cpc.ncep.noaa.gov

- Figure 3 - International Research Institute for Climate and Society - iri.columbia.edu

- Figure 4 - NOAA - Climate Prediction Center - cpc.ncep.noaa.gov