Nov 2016 La Niña Tracker

From the November issue of the CLIMAS Southwest Climate Outlook

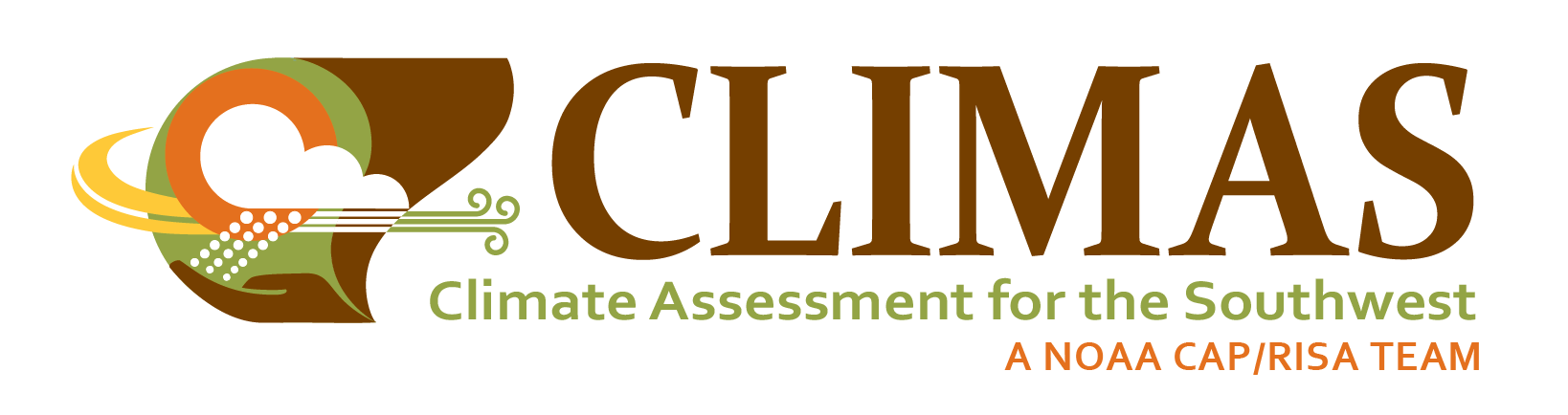

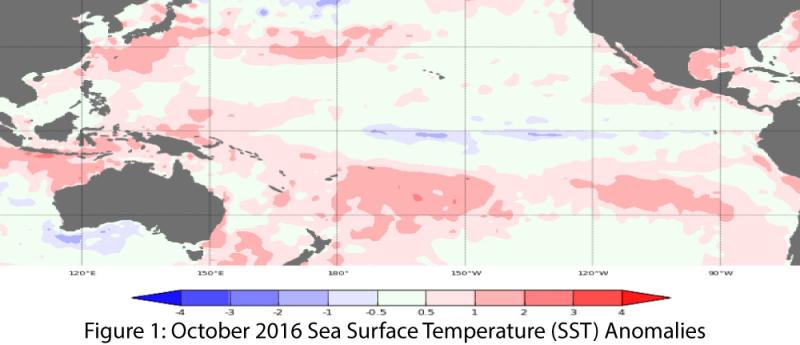

Oceanic and atmospheric indicators of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) continue to indicate the likelihood of a weak La Niña event this winter (Figs. 1-2), although the chance of an ENSO-neutral winter cannot be ruled out. Any hedging in the forecasts and outlooks likely stems from uncertainty as to whether the event will maintain even weak La Niña strength through winter 2017 (December–February). Fluctuations in forecasts and models are likely due to the limited coordination between oceanic and atmospheric conditions described in previous outlooks, as well as generally borderline conditions (i.e., between weak La Niña and ENSO-neutral).

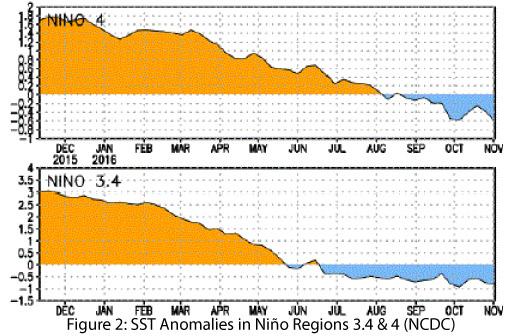

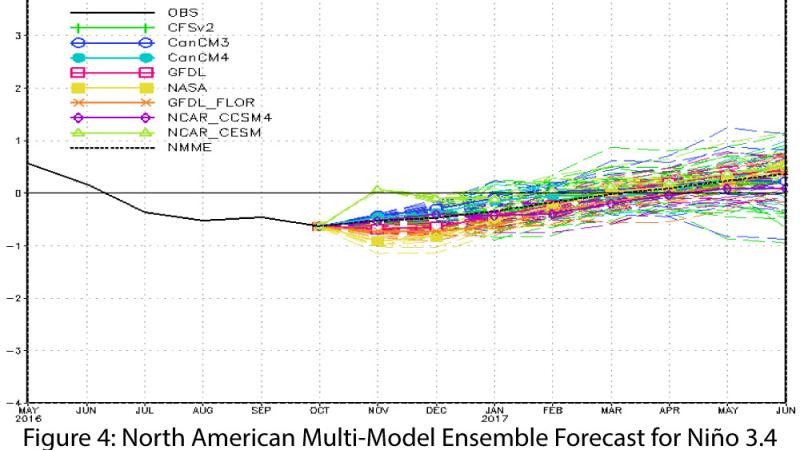

A closer look at the forecasts and seasonal outlooks continues to provide some insight into the range of expectations for a La Niña event this winter. On November 8, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology maintained its La Niña watch with a 50 percent chance of La Niña forming this winter—twice the normal likelihood—but also cautioned that La Niña events have only developed this late in the calendar year once since 1980. On November 10, the Japanese Meteorological Agency identified the ongoing presence of La Niña conditions in the equatorial Pacific and maintained its projection of a 60 percent chance of La Niña lasting through winter compared to a 40 percent chance of a return to ENSO-neutral conditions. Also on November 10, the NOAA Climate Prediction Center (CPC) identified ongoing weak La Niña conditions. The CPC indicated this event had a 55 percent chance of lasting through winter 2017 but that, generally speaking, it is expected to be short lived, with consensus focused on the event ending during or by the end of winter 2017. On November 17, the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) and CPC forecasts identified the emergence of a weak La Niña event that was likely to weaken further over the winter, and that would take very little to knock it out of La Niña status (“hanging on by a couple of toothpicks” according to Tony Barnston at IRI). The weak signal and uncertain future is captured in the Mid-Nov forecast that identifies a just over 50 percent chance of La Niña lasting through winter 2017, but with a rapid decline by spring 2017 (Fig. 3). The North American multi-model ensemble (NMME) characterizes the current model spread and highlights the variability looking forward to 2017. The NMME mean remains in the weak-to-borderline La Niña category through 2016 before returning to neutral conditions in early 2017 (Fig. 4).

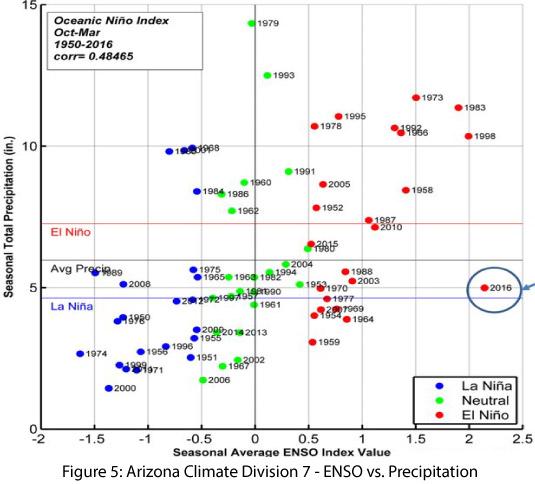

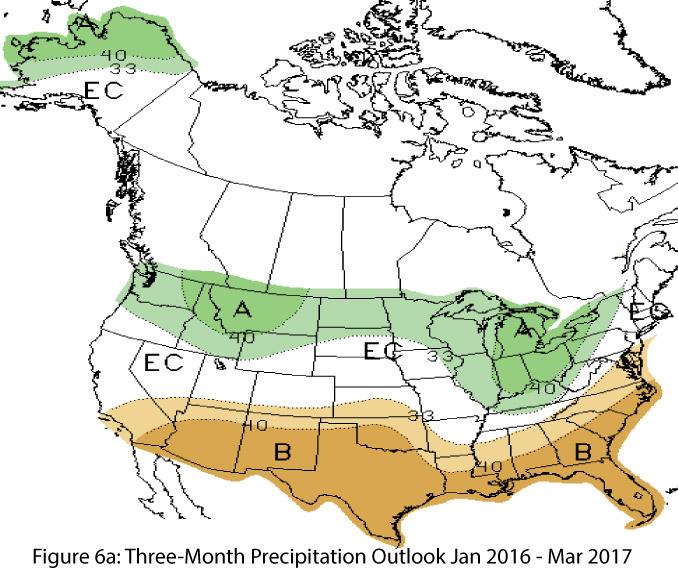

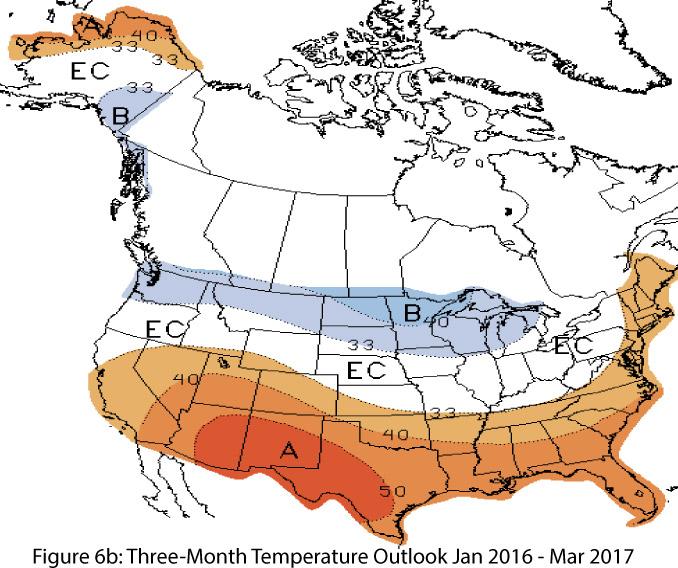

La Niña remains on the horizon for the Southwest in winter 2017, with current forecasts indicating a weak La Niña event during winter 2016–2017, which is more likely than not to bring warmer- and drier-than-average conditions to the region over the cool season. Even if the event decays more rapidly than forecast and conditions tack back toward neutral conditions, borderline La Niña conditions still could affect temperature and precipitation patterns through the winter. Southwestern winters already are characterized by a relatively dry climate (i.e., limited precipitation events over the cool season), and a La Niña event has the potential to shift that seasonal pattern to an even drier state. While considerable variability exists in precipitation totals during ENSO-neutral years, La Niña years tend to cluster on the dry end of the distribution (Fig. 5). Seasonal forecasts likely were already incorporating the influence of La Niña into monthly and seasonal forecasts, and if La Niña does persist, even in a weak form, we can expect these forecasts will continue to suggest warmer- and drier-than-average conditions (Figs. 6a-b).