Exploring Children’s Drawing as Ecological Engagement

Six-point stars in bright purple, sunshine yellow anthers. Fuzzy grey-green leaves with crinkled edges.

Clusters of purple slippers, then spiraled pods. Soft green leaves, in groups of three.

Fat black bees with metallic wings. Grasshoppers, camouflaged in every shade of green and brown.

A rustle in the leaves, then a whip of a tail.

At first, the field looks to be just a messy patch of green, bordered by dry brown dirt with a few pokey weeds. But as we look, and look some more, our eyes adjust. We start noticing the irrepressible silverleaf nightshade alongside the sweet aroma of alfalfa. We realize the bees are far too busy to pay attention to us, and, if we crouch down into the greenery, the grasshoppers look right back at us. If we’re quiet and still, we might glimpse a lizard or two.

I’m knee-deep in this summer field, ostensibly grown for alfalfa but boasting thick tangles of bindweed, amaranth, and various grasses too. A group of children wander the field with me. Some carry magnifying lenses, but mostly they just press their faces up to small wonders. At the moment we’re investigating plant parts, prompted by the question, “What can a leaf do?” At first, the kids offered a few ideas derived from half-remembered school science lessons, but it quickly became clear that in order to answer this question, we must go spend time with plants and their leaves.

Figure 1. Children explore an alfalfa field on a New Mexico farm.

It’s mid-week of a science camp at a working farm in Albuquerque, NM, the collaborative effort of a family-centered science museum, Explora, and the local agricultural community hoping to engage the next generation. For the past eight years I have worked for the museum as an educator, an immensely gratifying job of facilitating lifelong learning opportunities for children and families both inside and outside of the museum, and working with education professionals to enrich K-12 school curriculum. Explora’s approach to learning values hands-on inquiry, learner agency, and connections to everyday life. This small farm, one of many in the traditional agricultural community in this verdant stretch along the Rio Grande, provides an unconventional learning space but one in line with Explora’s pedagogy. Nearby, only a short walk along the acequias (a traditional community-operated irrigation system), are other family and small-scale farms, community gardens, and farmers who work hard to provide food for the community and care for the land.

In 2017 I began designing and facilitating STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, math) curriculum for Explora to get kids out of indoor classrooms and into the bosque, the nearby riparian cottonwood forest lining the Rio Grande. I was motivated by my background as an interdisciplinary artist, a robust interest in natural sciences and environmental issues, and a curiosity for others’ relationships with place and the creative impulses they inspire. This work eventually led to my PhD journey at the University of Arizona in Art and Visual Culture Education.

Two years later, I helped Explora launch a pilot program of science-based environmental education in partnership with the local agricultural community, beginning with day camps for K-5th grade at a working farm. Despite the ensuing pandemic, the program blossomed into seasonal and year-round education and outreach opportunities involving schools, out-of-school-time programs, farmers, and others committed to maintaining agricultural heritage and sustainable agriculture futures. Through listening sessions with our community partners, my fellow Explora educators and I worked to develop learning activities and curriculum based on topics identified as most relevant or significant to the goals of the community, such as soil and compost, pollinators, botany, water and hydrology, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). We then shared these resources with the broader community in digital and nondigital forms to connect children and families to backyard ecologies and local agriculture. We integrated these ideas into Explora’s existent programming as well. Many of the partners contributed in other ways: virtually visiting school classrooms, donating soil and seed samples, hosting field trips, and providing learning spaces.

Figure 2. Children learning about chile farming in New Mexico.

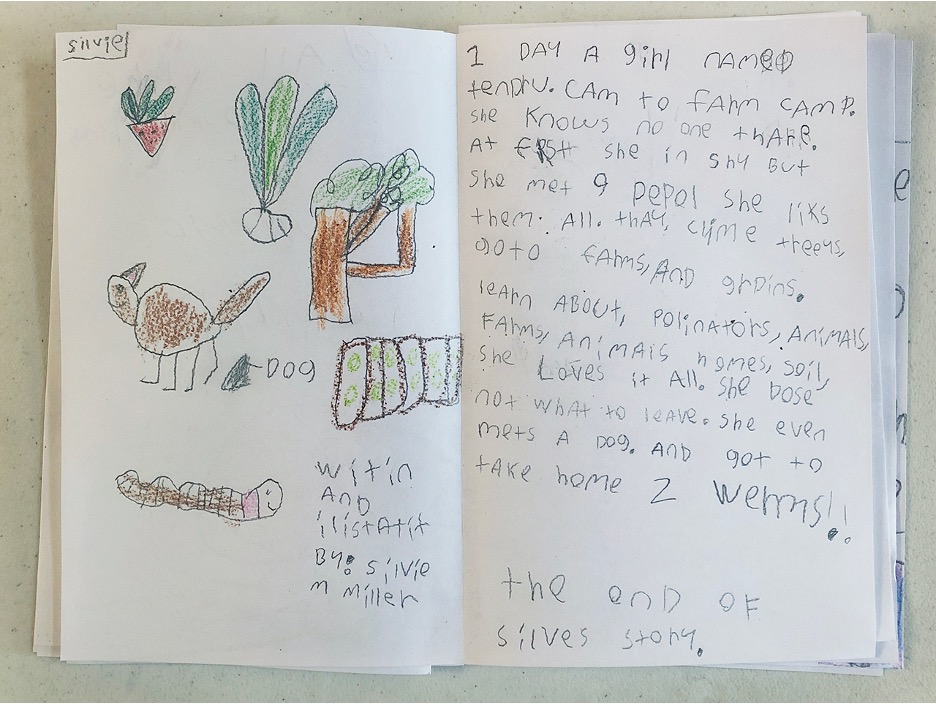

For me, the most interesting thing happens when children are immersed in the ecology of a living space. Out in the field, amid the banquet of nectar, the clacking grasshoppers, and droning bees, the kids learn with the nonhuman community, not just about them. This is affective stuff—these encounters become part of how these kids come see the world, for what they tend to notice and carry on. I know this because threads of these experiences often resurface in the kids’ drawing practices, and how they use visual symbols and gestures to actively create and communicate their knowledge. Drawing, especially for children, is so much more than scribbles or aesthetic rendering; it’s expression, sense-making, representation, observation, and participation. In short, it’s a form of attention to the world.

Figure 3. A child carefully draws a leaf.

My dissertation research focuses on this phenomenon of drawing and its tie to relational ecological identity, or the development of kinship with the places we inhabit. While the efforts of Explora and the agricultural community help facilitate opportunities to learn in this way, it’s crucial to understand plants, animals, and place as key teachers. I’m seeking to understand more about relationships between human learners and nonhuman teachers, and how the capacity of drawing functions as a vivid dialog and artifact of this relationship. Participant observation, visual ethnography, and multispecies ethnography all play roles in working to understand the complexity of these relationships.

Figure 4. A child's drawing about learning on a farm.

Findings from this research aim to help educators like me design more socially and ecologically responsive curriculum and teaching practices that support children’s intellectual and emotional capacities. In turn, these approaches can help build relational ecological identity and capable response to environmental issues. We can then share these insights through educational resources to be used at a museum, home, school, or other learning setting. It’s important to center drawing as a mode of learning because of its support of cognitive development and imaginative possibilities. In other words, the processes involved in drawing can help children make sense of and answer questions about plants, leaves, or anything else, in infinite ways.

The sun is reaching high in the sky and the cicadas have overtaken the sounds of the field. We retreat to shade where the morning’s discoveries and adventures will perhaps reappear, transformed, on paper in technicolor lines and shapes.