Caring in Crisis: Challenges and Lessons in Practicing Collaborative Research in 2020

Regenerate Hub

My CLIMAS fellowship project was geared towards building a web platform called “Regenerate Hub” that provides data visualization and collaborative tools to enable diverse stakeholders to take action on interconnected social, environmental, and infrastructural problems. I am a doctoral candidate in anthropology and I met my community partners for this project, Recycle Lebanon, through my preliminary dissertation research. This research was investigating how people were intervening in Lebanon’s greatest challenges through altering and repairing infrastructural systems such as waste management. Recycle Lebanon is a small Lebanese nonprofit organization that emerged in response to the garbage crisis in Lebanon that peaked in 2015. They began by designing campaigns to clean garbage from coastlines, waterways, and forests, a movement which grew to include establishing the first zero waste shop in the Middle East (the EcoSouk) and innovating ways to reuse waste such as cigarettes through creating the first cigarette recycling initiative in the country.

Photo 1: Planning meeting for Regenerate Hub, Summer 2019 (Credit: Rachel Rosenbaum)

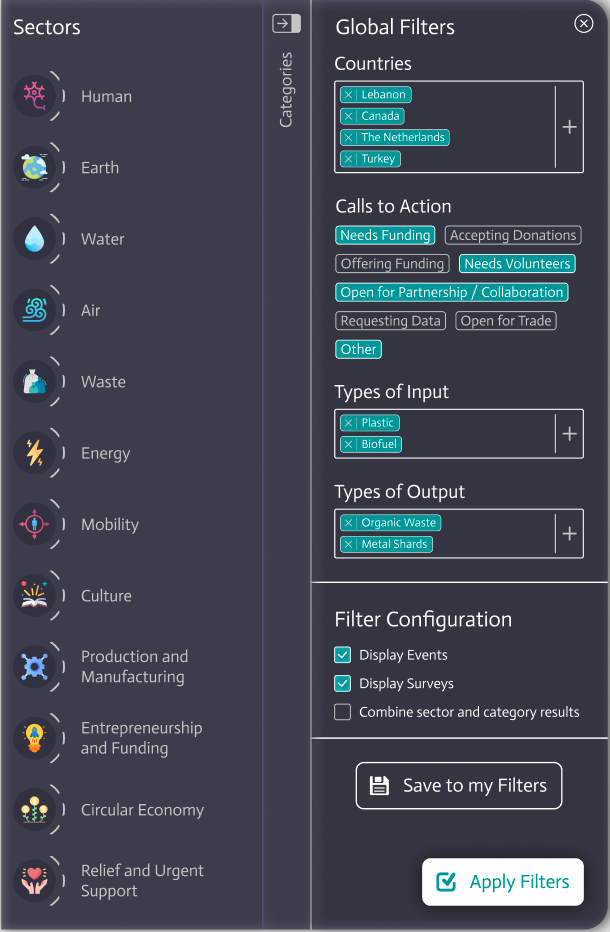

I began volunteering with the organization specifically to work on their ongoing data collection efforts to build “Regenerate Hub” under their program called “Regenerate Lebanon”. Regenerate Hub is an online platform aiding in conscious system change with a mission to strengthen the circular economy and promote sustainable development solutions. The site tackles interconnected social, economic, and environmental issues by promoting access to information, integrating opportunities for action, visualizing data, and incentivizing users to scale game-changing solutions by means of interconnectivity across sectors and encouraging nature-based solutions. The platform will guide multiple stakeholders to engage, visualize, and interact with service providers and disparate datasets and publications retrieved from researchers and institutions. The various features will include robust data filtration, data mapping and visualization, a library of publications and resources, and the ability for users to contribute data, validate data, and download data. There will also be robust user capabilities such as the ability for users to connect on topics in forums, save their data searches and pins, and tools for users to collaborate on new projects.

Photo 2: Field visit to local NGO who collects and sorts recyclables (Credit: Rachel Rosenbaum)

The main goals of the site are:

- To aggregate and enable access to data regarding up-to-date socio-environmental problems and local solutions

- To provide tools to directly connect sectors with beneficiaries to innovate solutions to socio-economic issues while building connections between stakeholders that will allow people to collaboratively develop solutions online and offline.

- Provide the data and technical information to aid in industrial transitions towards regenerative systems and a circular economy (i.e. reducing single use plastic use and disposal, designing non-recyclable materials out of production)

- To promote and facilitate actions for people to invest resources, knowledge, and action to slow climate change and regenerate natural resources.

Using methods in qualitative and quantitative data collection, we’ve focused on aggregating data with various partners in the sectors of waste, energy, agro-business, and sustainable production and manufacturing. As the project evolved, I took on a product management role, deploying methods in ethnography and human-centered design to create the data visualization schema and in collaborating on the user experience design for the website. When I left Beirut in August 2019, I was planning to return in May 2020. We had agreed that I would remotely continue efforts to raise funds for web development costs and continue data collection efforts until I returned for my long-term fieldwork in Lebanon. However, this plan was soon interrupted and we have battled to continue this collaborative project through a political revolution, a global pandemic, a horrific explosion in Beirut, infrastructural challenges, and an economic crisis.

Photos 3: Solar panels and water tanks set up by Regenerate Lebanon and partners (Credit: Recycle Lebanon)

Facing the Unique Challenges of 2019 - 2020

Starting in October 2019, a political revolution in Lebanon (or thawra in Arabic) called for the resignation of the government and the dismantling of the governing elite. This was catalyzed by impending austerity measures which combined with decades of frustration over sectarian-based resource distribution practices, corruption, and chronic failure to provide for basic public needs and develop working infrastructures. While there have been political revolutions in Lebanon before, this was the first post-civil war movement that has not conformed to a sectarian status quo. Grassroots, decentralized, and nonsectarian co-occurring movements across the country were successful in overthrowing the Prime Minister and the formation of a new government (Chehayeb and Sewell 2019). It was within this revolution that I was awarded the CLIMAS fellowship for the “Regenerate Hub” project with Recycle Lebanon in December 2019.

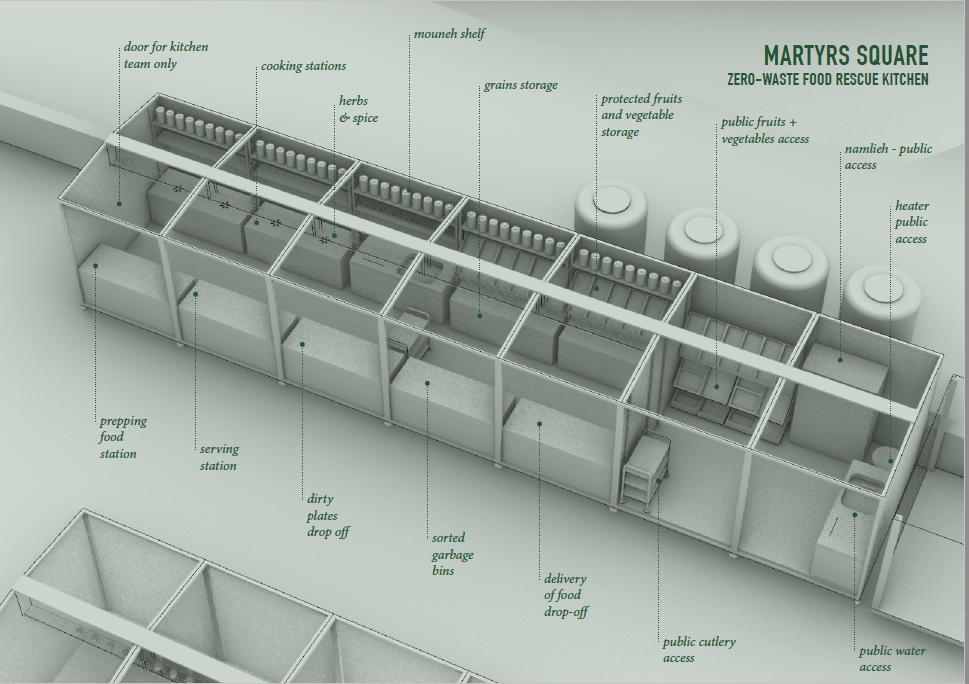

During the thawra, the Regenerate Lebanon initiative took on new life as many people were collaborating within daily protests to reclaim public spaces and create community spaces. Regenerate Lebanon set up a pilot physical infrastructure that mirrored the goals of the “Regenerate Hub” online platform. In Martyr’s Square in downtown Beirut, Regenerate Lebanon set up a tented village with waste collection and recycling services, solar energy, composting, potable water, a zero-waste kitchen to provide free meals, a donation collection station to redistribute goods, and collaboration/co-working spaces where people hosted events and created new projects.

Photo 4: The site of a zero-waste holiday thawra dinner thrown by Regenerate Lebanon and partners (Credit: Recycle Lebanon)

However, within the middle of this national uprising, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. In March 2020, as coronavirus spread across the globe, the Lebanese government initiated a lockdown of the country with strict curfews. The pandemic gave the government an opportunity to re-entrench power along sectarian lines and undercut the political gains of the thawra. For my research collaborators, this represented a considerable loss. At the beginning of the lockdown, military and police forces destroyed the public spaces and infrastructures in the thawra village and labelled remaining anti-government protesters as bioterrorists (Perry 2020). The army and police raided downtown public squares where they destroyed tents, food trucks, and confiscated other public infrastructures while detaining and fining protestors who remained in public spaces. Recycle Lebanon had to try to salvage the materials from the Regenerate village and shut down operations of this space.

The first two months of quarantine became an essential space of rest from the demands of activism for many in Lebanon and a time to process what politics may look like in the aftermath of the lockdown and the loss of the physical spaces they built. With the quarantine in full force, the first version of “Regenerate Hub” was launched online, building on the momentum of the thawra. I continued to work remotely and was able to regularly participate in meetings online as our world continued to shift.

Photo 5: Rendering of the Zero-waste kitchen in thawra (Credit: Recycle Lebanon)

With deteriorating economic conditions around the world and a currency crisis in Lebanon, we faced significant challenges in continuing to create Regenerate Hub alongside our other personal and professional pursuits. As Recycle Lebanon is a very small organization, they have relied on volunteer labor or partnership collaboration to carry out their projects. The latest economic challenges led to personnel changes as people around the country were economically displaced within and from Beirut. Much of the team disintegrated and we had to rebuild the team. Our previous small budget for web development no longer became feasible nor did we feel volunteer labor from those experiencing such financial harm was ethical. We spent Summer 2020 fundraising to be able to carry on. Thankfully, we were awarded a grant from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) funded by the Japanese Embassy in Lebanon to fund the web development of Regenerate Hub with a Beirut-based group and with GIS mapping support from Arizona Institutes for Resilience (AIR) at the University of Arizona.

Yet, we soon faced another setback. On August 4th, 2020, one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history decimated Beirut (Amos and Rincon 2020). Over 190 people died, 6,500 were critically injured, and over 300,000 displaced overnight. Investigations reveal that the explosion was a human-produced disaster resulting from the combustion of nearly 3,000 tons of ammonium nitrate improperly stored in the Beirut port for nearly a decade (Forensic Architecture 2020). As I was beginning my comprehensive exams in Arizona, my friends and colleagues were sending me photos and stories of the impacts. The pictures of the apartment I live in when in Beirut are unsettling: bed sheets blasted across the room, shattered glass everywhere, pictures on the floor strewn from their frames, my roommate’s full coffee cup from the morning somehow intact. Other homes look as if their faces have been ripped off, providing a rare glimpse of the life behind the façade. Each uncanny scene of the rubble, the debris of dreams and lifeworlds, appeared haunted; haunted by the state, by colonization and neoliberal technocrats, by wars and greed and environmental destruction.

The effects of this traumatic event will be felt for decades to come and pervades any experience of trying to return to normalcy for both my colleagues in Lebanon and for me, living over 11,800km away. Existing economic challenges and infrastructures have further deteriorated, with frequent electricity outages, food shortages, difficulty accessing bank funds, and skyrocketing prices for basic goods. Our new normal in building Regenerate Hub looks like many things: Zoom meetings conducted in darkness, across time zones; creative solutions to persist through Wi-Fi outages; laughing at one another’s quarantine wardrobe choices; listening to one another’s challenges; learning to trust in the wake of trauma; communicating our needs; appreciating the small wins; building friendships.

Photo 6: Post-explosion damage in Beirut (Credit: Jo Kassis via Pexels)

Lessons Learned

This year, more than most, has underscored the importance of fostering networks of care and trust and cultivating reflexivity in collaborative research. This year I have been privileged to maintain a paying job and the ability to work remotely to keep myself and my loved ones safe, an advantage that many are not afforded. All the while, I have witnessed the acute challenges and trauma in the lives of my friends and colleagues in Lebanon as they watched their government continue to fail them, their homes disappear, and the city they love crumble to the ground from the government’s negligence and corruption. I too have grieved the beloved places in Beirut I will never get to visit again and the futures myself and my colleagues will no longer have. I too have grieved my own government’s negligence in battling a pandemic that disproportionately impacts people based on race and class and the demonization of struggles for racial justice. The disparate reality of experiencing 2020 is representative of violent colonial histories between the global north and south, a relationship that I believe researchers have a responsibility to redress.

Reflecting more deeply on this has made me change how I approach research in general. Rather than focusing on research outputs, I believe collaborative research necessitates a focus on process and power. As a result, I have intentionally leveraged my institutional resources and knowledge for this project, given my labor freely, and held space for my colleagues who are impacted differently than me in these times. I have also found that the shared challenges we all face in just trying to continue to live and work in these times have created more understanding of the need to displace the focus on “productivity” in work. In our work, we need more time to grieve, time to take care of our (mental) health, to rest, and to connect in times of isolation.

What Comes Next

Since September 2020, the team has rebuilt and been able to focus on designing Regenerate Hub to be as impactful as possible. We are on track to finalize the first phase of development and re-launch the site by the end of February 2021 with the full site functionality to be up and running by June 2021. I hope to return to Lebanon in Summer 2021 to conduct dissertation fieldwork on the politics of infrastructure in Lebanon and will continue to work on the development of Regenerate Hub.

Despite all the challenges of this past year, I am immensely encouraged by the resilience and growth of this project and the people who have built it. One of the main successes of this collaboration has been a renewed sense of care and strengthening of not just partnerships, but friendships.

Photo 7: Wireframe mock-up of Regenerate Hub filtration page overlayed onto the main map (Credit: Recycle Lebanon)

Photo 8: Wireframe mock-up of Regenerate Hub – detailing sectors, “calls to action” functions, and material inputs and outputs which will allow researchers and producers to track material flows (Credit: Recycle Lebanon)