Monsoon Extremes, Past and Future

We’re all itching to know if the monsoon will deliver this year, especially with the record wildfires, the widespread drought, and the closure of national forests across Arizona and New Mexico. To pass the time before the monsoon moisture arrives, I’ve been taking a look at monsoon statistics for Tucson. Here the wettest monsoon since 1900 was in 1964, when we got 13.84 inches!The driest year was 1924, when the city only received 1.59 inches (the average amount of monsoon precipitation for the city is about 6 inches).

Since our records of rainfall only go back to 1900, it’s hard to tell if the monsoon could get even stronger, or weaker, or if there could be periods of persistently strong or weak monsoons (e.g., ten years in a row of weak monsoons). To get at this information requires longer records of monsoon variability. Luckily, there are many archives of climate in the natural world. One of the most well known of these is tree rings. The width of the ring a tree puts on each year is a function of climate: often warmer temperatures or more moisture will produce wider rings, and cooler or drier conditions will produce narrower rings.

Capitalizing on this climate /ring-width relationship, climate and tree-ring scientists have recently begun to investigate reconstructing the history of the monsoon from trees in the Southwest. I sat down to talk with my friend, Dan Griffin about this new field of inquiry. Dan is conducting his dissertation research with Connie Woodhouse, Dave Meko, and other climate and tree-ring researchers at the University of Arizona (visit their research web site).

Dan works on Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir from Arizona and New Mexico--the core region of monsoon influence in the United States. These two widespread tree species have a strong relationship with precipitation in this area. But usually, tree-ring width in these trees responds more strongly to winter precipitation, which makes it hard to extract a signal of summer precipitation. To get at summer precipitation Dan is taking his analysis one step further than just measuring tree-ring width and extracting an annual record of precipitation.

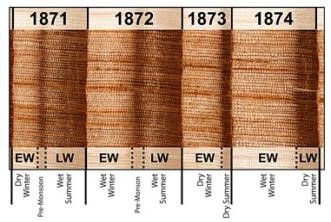

It has been known for a long time that tree rings contain both ‘earlywood’ and ‘latewood,’ and recently, tree-ring researchers have realized that measuring these two components of tree rings separately provides a record of climate change in different seasons. In Dan’s trees, earlywood ring width responds to winter precipitation, and latewood ring width responds to summer precipitation. Thus, Dan has been able to produce a record of past summer precipitation for our monsoonal region of the Southwest. Pretty cool stuff.

Dan presented his findings at the most recent AGU meeting last winter. Some interesting results so far are that the 20th century has been somewhat unique compared to the last 350 years in that there weren’t any periods of persistently dry monsoons—meaning several years in a row of weak monsoons.

Before the 20th century, there were more periods of dry monsoon after dry monsoon, especially in the 1880s up until about 1905.

So, all this climate history is interesting for climate nerds, but why is any of it importance to everyone else? As Dan puts it, in the future, monsoon rainfall will be even more important for the Southwest since winter precipitation is projected to decrease with increasing greenhouse gas concentrations. But what is projected to happen to monsoon precipitation? Unfortunately, we don’t know yet. The global climate model simulations forced with projections of how much greenhouse gas emissions we’ll be emitting in the future do not have high enough resolution to simulate our monsoon. Smaller-scale, ‘regional’ climate models can simulate the monsoon and results from these types of models are in the pipeline, but how will we know if they are doing a good job? If the models can produce the types of monsoon variability we saw in the 20th century, and in the tree-ring record of the monsoon prior to the 20th century, then we’ll be able to trust their projections, and hopefully adapt to the monsoon of the future.