Monsoon Tracker & Hurricane Bud

*The following summary is adapted from the June 2018 issue of the CLIMAS Southwest Climate Outlook.

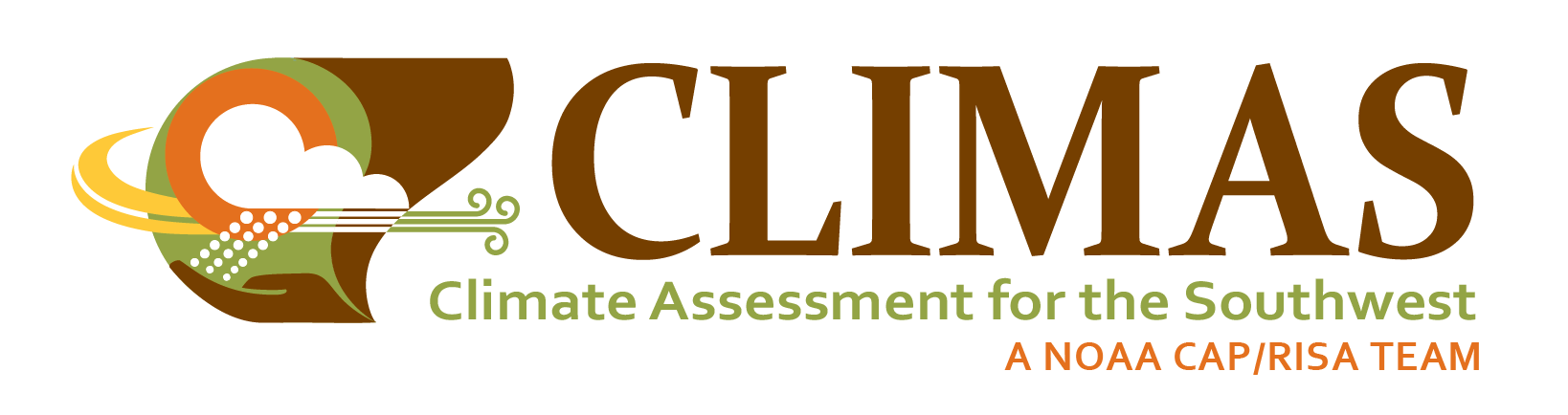

Monsoon season has officially begun in the Southwest U.S and northern Mexico. In 2008, the U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) changed the definition of the start of the North American monsoon from a variable date based on locally measured conditions to a fixed date of June 15th. Prior to 2008, the start date reflected the seasonal progression of the monsoon (Figure 12), based on larger seasonal atmospheric patterns.

Figure 12: Historical Monsoon Onset Date. Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology

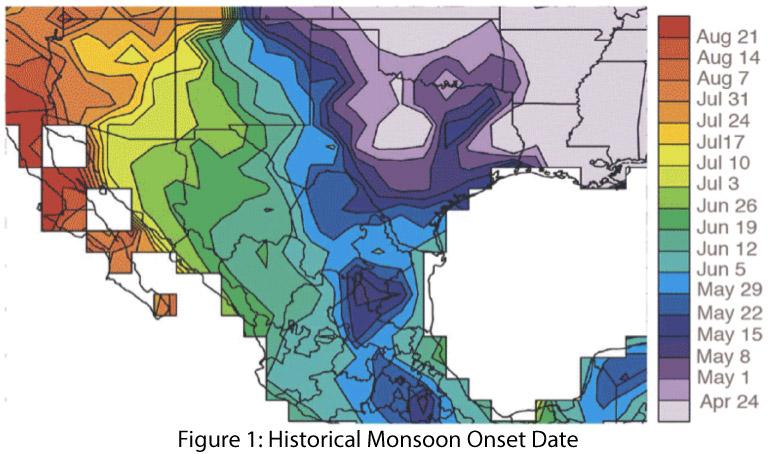

This gradient is linked to seasonal atmospheric patterns and the establishment of the ‘monsoon ridge’ in the Southwest (Figure 13). The heating of the complex topography of the western U.S. with the increasing sun angle and contrast with the cooler water of the adjacent Pacific Ocean lead to the establishment of this upper-level ridge of high pressure over the Southwest U.S. (also known as Four Corners High). This flow around this upper level ridge shifts from a dry southwesterly fetch in May to a moisture rich southerly-southeasterly fetch in late June/early July.

Figure 13: NCEP/NCAR Mean 500mb Geopotential Height (1948-2007) – June (left), July (right).

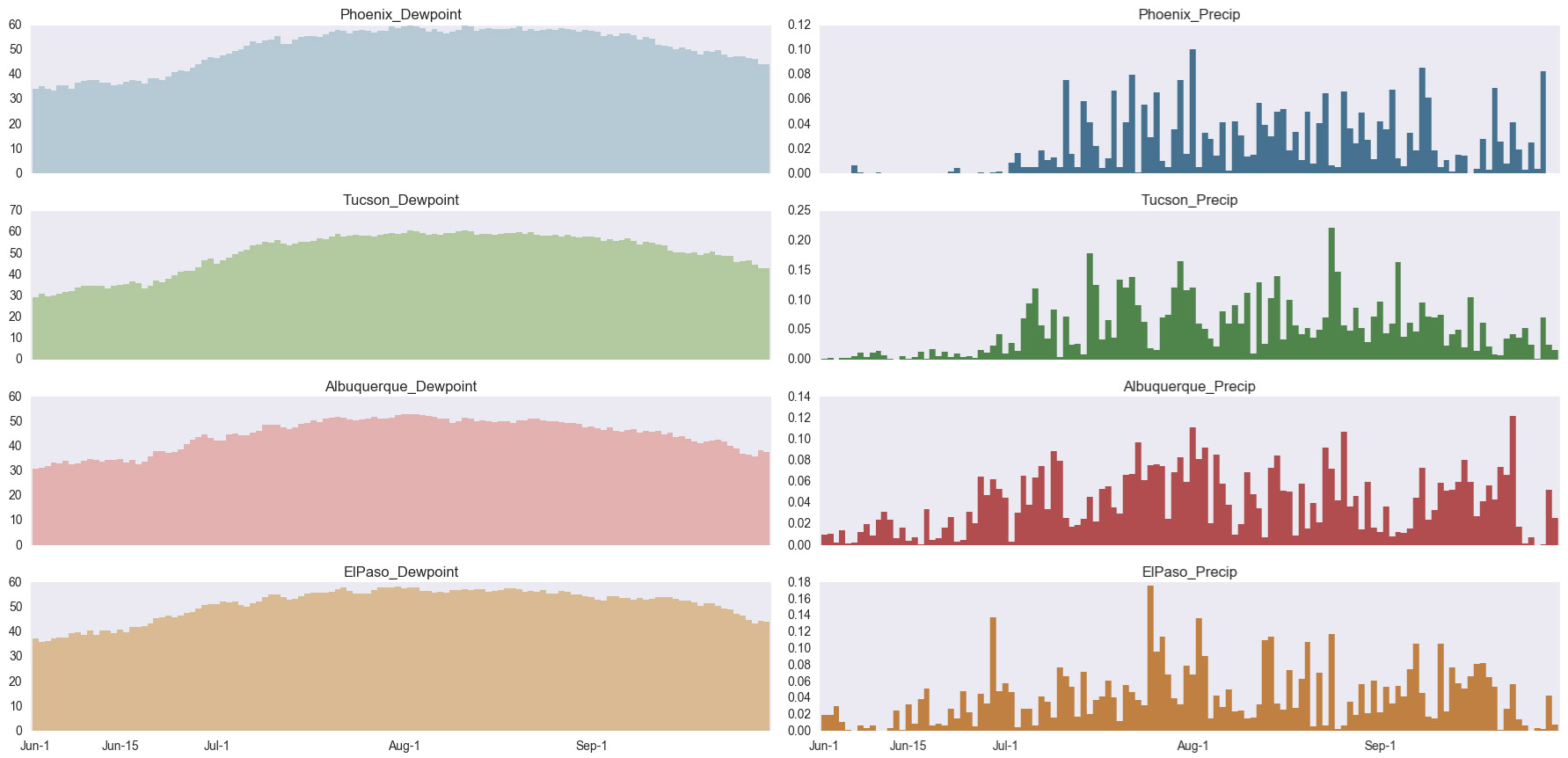

In southern Arizona, the start date was originally based on the average daily dewpoint temperature. Phoenix and Tucson NWS offices used the criteria of three consecutive days of daily average dewpoint temperature above a threshold (55 degrees in Phoenix, 54 degrees in Tucson) to define the start date of the monsoon. The average daily dewpoint temperature is still a useful tool to track the onset and progression of conditions that favor monsoon events, and the NWS includes a dewpoint tracker in their suite of monsoon tools.

Thirty-year averages for daily dewpoint and precipitation demonstrate the gradual increase in dewpoint temperatures during the monsoon season, as well as the variability of precipitation observed over the same window (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Average daily dewpoint temperature (left) and average daily precipitation (right).

Figure 14: Average daily dewpoint temperature (left) and average daily precipitation (right).

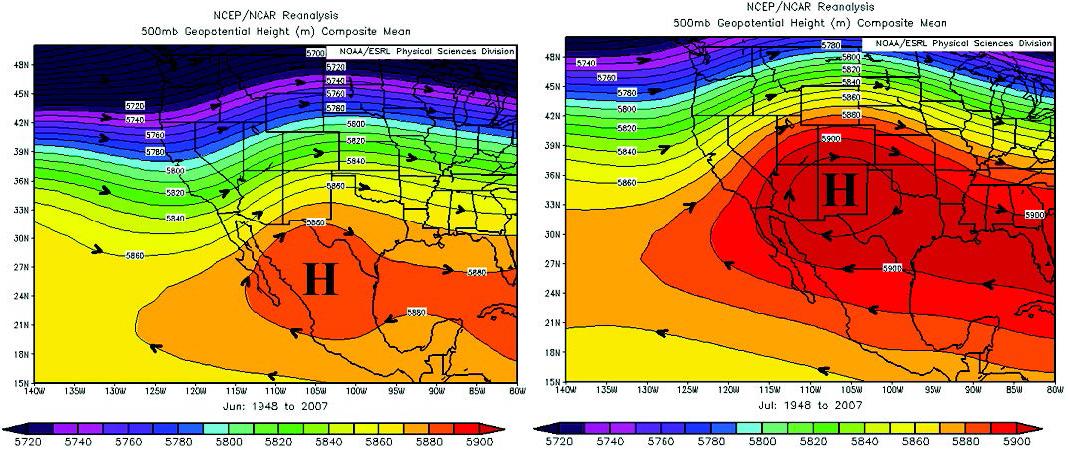

The updated definition of the monsoon identifies a season that lasts for 108 days with defined start and end dates of June 15 and Sept 30. Dewpoint and precipitation may provide a more granular assessment of monsoon activity, but the seasonal designation allows for easier comparisons between years and focuses planning activities on a discrete monsoon season. Although monsoon storm activity begins in June for Albuquerque and El Paso, the majority of activity occurs in July and August (Figure 15), with some lingering activity into September (occasionally augmented by eastern Pacific tropical storms). Thus, the recent incursion of moisture from Tropical Storm Bud was a welcome change to the typical mid-June dry heat. Arriving on June 16th for southern New Mexico and West Texas, Bud raised the question: Did this moisture qualify as “monsoon”?

Figure 15: Average monthly monsoon precipitation in the Southwest U.S.

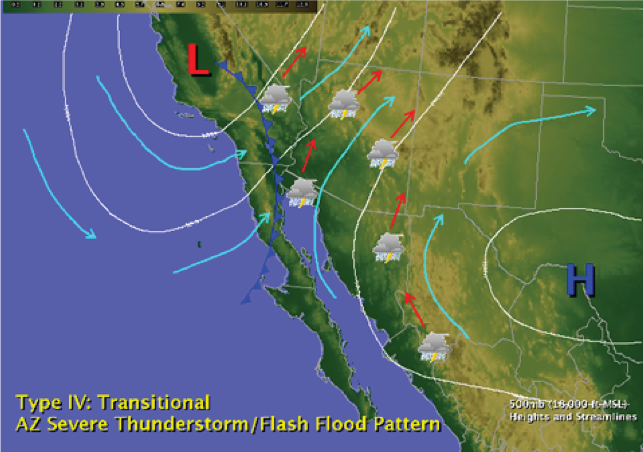

The moisture from Tropical Storm Bud was key to the widespread event, but the rain also was dependent on a low-pressure system that happened to be nearby. Bud was caught between a trough of low pressure off the coast of California and the subtropical ridge which was displaced well to the east over the Gulf of Mexico. The flow pattern over this event resembled a ‘transition’ pattern typically seen at the end of the monsoon season (Figure 16), when the mid-latitude jet stream becomes more active and the monsoon ridge starts to retreat south. Together these features helped guide the storm into southern New Mexico and West Texas.

Figure 16 (above): Type IV Monsoon Transitional Pattern (Source: NWS Tucson)

The approaching trough of low pressure was also critical to cooling upper-level air temperatures, increasing the instability of the very moist airmass at the surface, and providing wind shear to help organize any storms that formed. This kind of assist is possible at the beginning of the monsoon in June but is much more common in late summer when we are transitioning out of the monsoon. It rarely occurs in the middle of the monsoon because of the dominance of the subtropical ridge pattern that limits how close mid-latitude storms can get to the Southwest.

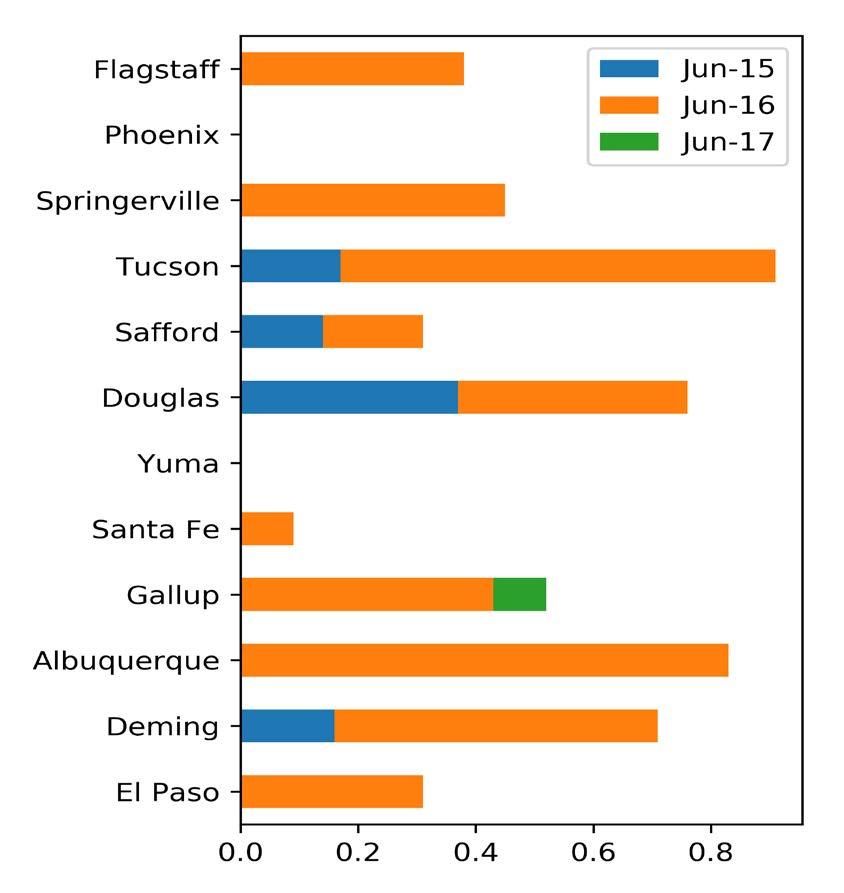

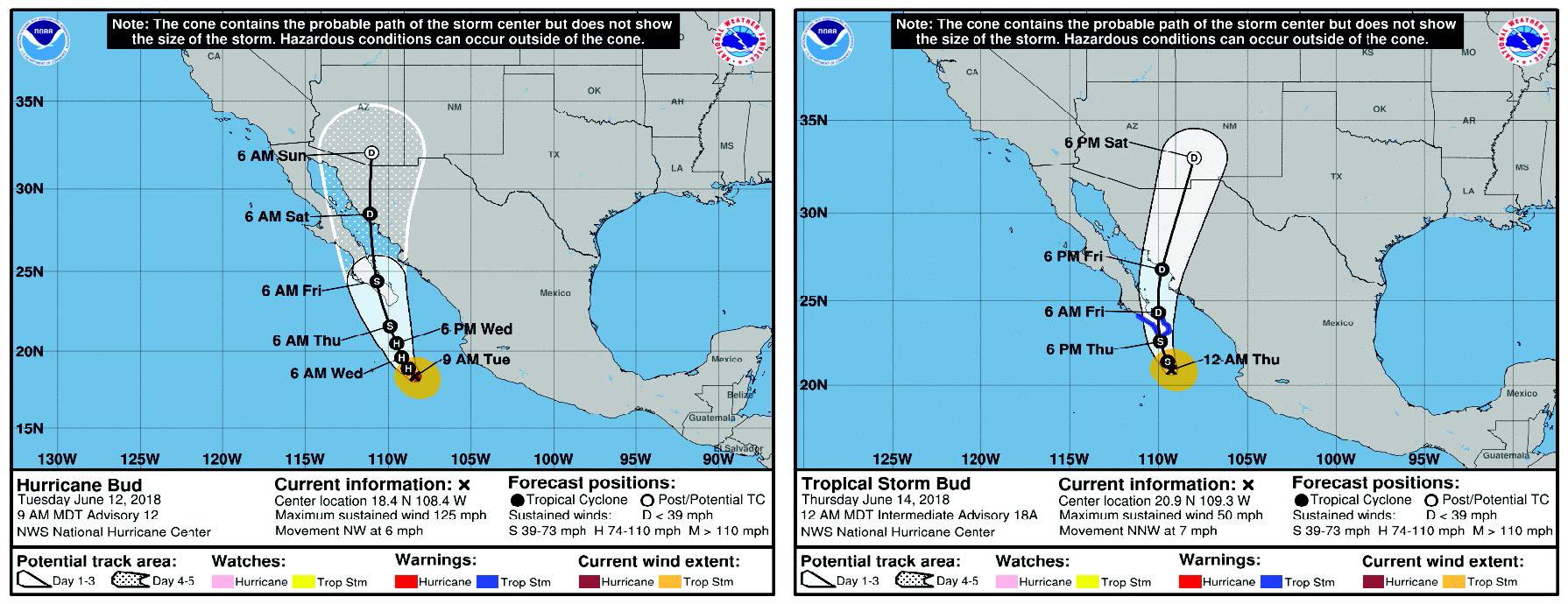

Ultimately, the storm was less dependent on the exact track that Bud took in mid-June (Figure 17), and more dependent on larger atmospheric patterns that came together to bring welcome – if unexpected precipitation to the Southwest. Figure 18 shows storm totals for some cities in the region.

Figure 17 (above): Hurricane/TS Bud – National Hurricane Center Advisory Maps for June 12 (left) and June 14 (right).

Figure 17 (above): Hurricane/TS Bud – National Hurricane Center Advisory Maps for June 12 (left) and June 14 (right).

Figure 18 (left): SW Regional Storm Totals – June 15 – 17, 2018.

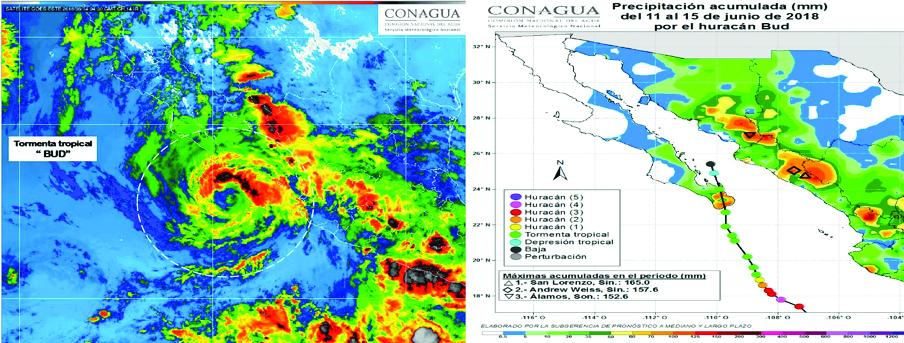

Hurricane Bud, which reached category 4 by June 12, entered the southern Baja California Peninsula as a tropical storm on June 15. Cloud bands covered portions from central Sinaloa to southern Sonora, leaving the highest accumulations of rainfall between June 11 and 15 of 6.5 inches (165.0 mm) in San Lorenzo, Sinaloa; 6.2 inches (157.6 mm) in Andrew Weiss, Sinaloa; and 6.0 inches (152.6 mm) in Alamos, Sonora (Figure 19).

Additional Monsoon Resources:

• NWS: http://www.wrh.noaa.gov/twc/monsoon/monsoon_info.php

• CLIMAS: http://www.climas.arizona.edu/sw-climate/monsoon

• CONAGUA: http://www.gob.mx/conagua/prensa/inicio-el-monzon-de-norteamerica-en-el-noroeste-de-mexico

Figure 19 (above): Cloudiness associated with hurricane / tropical storm Bud (left). Total rainfall from June 11 to 15, 2018 by the passage of Bud (right). Cyclonic trajectory obtained from the NHC, satellite image and rain data of the SMN.