El Niño Tracker - December 2014

2014-15 El Niño Tracker

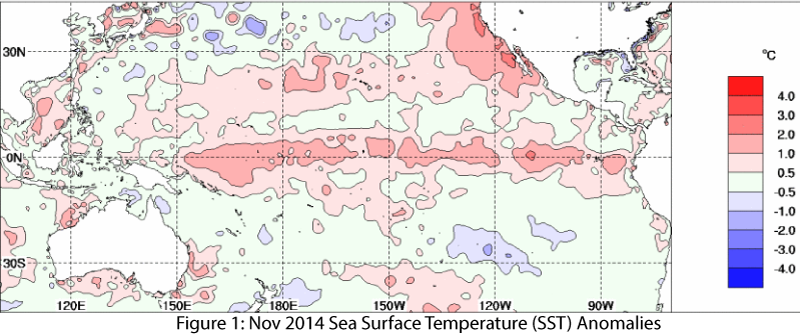

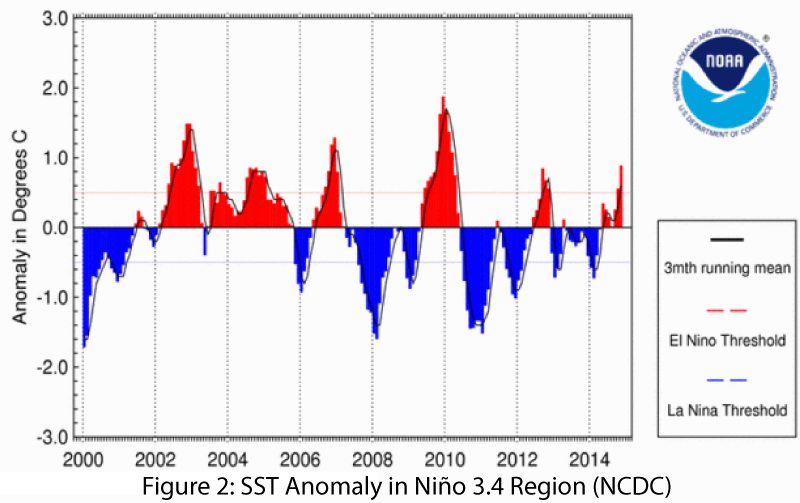

We are still waiting for a decisive signal, but conditions indicate we are near, or possibly already into, at least a weak El Niño event. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are elevated across the equatorial Pacific Ocean (Fig. 1), and the measurements in the Niño 3.4 region are indicative of El Niño having already started (Fig. 2). There remains a distinct lack of cooperation on the part of the atmosphere. This lack of coupling between ocean and atmosphere (demonstrated by near-normal wind and rainfall anomalies), along with a lack of temperature gradient along the equatorial Pacific and little in the way of El Niño wind patterns, means that while we are likely already experiencing El Niño-like conditions in the Southwest (e.g. some of the recent wet weather), it may be a little longer before a formal declaration occurs, even if retroactively.

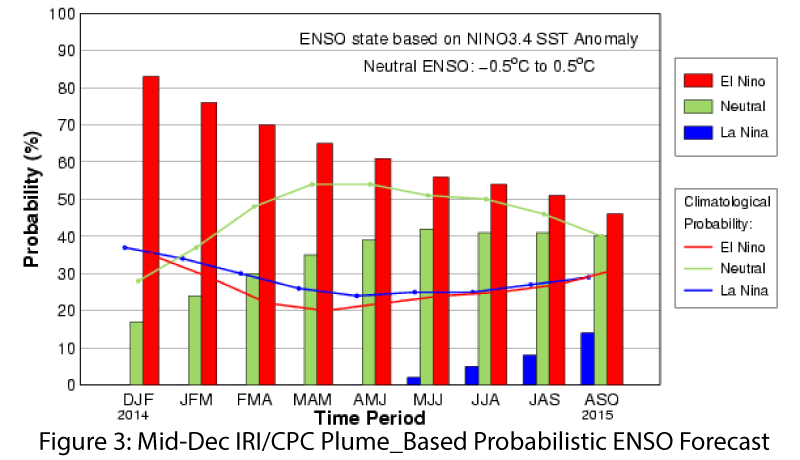

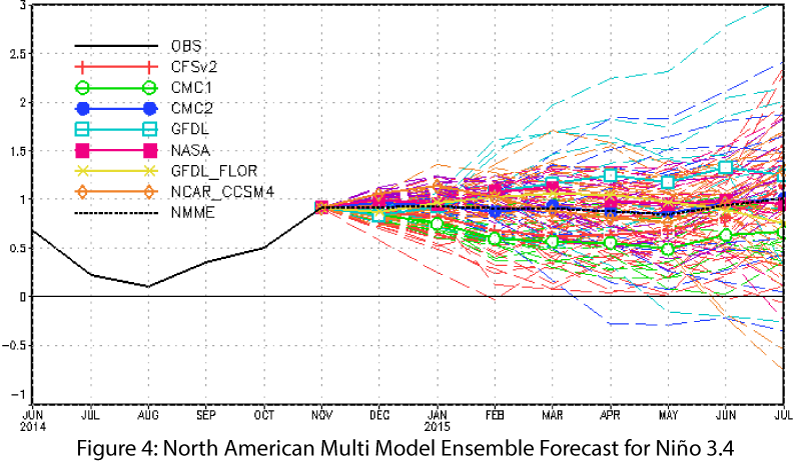

On Dec. 4, the NOAA-Climate Prediction Center (CPC) issued another El Niño Watch, with a 65 percent probability of a weak El Niño event occurring. Anomalous SSTs alone were probably enough to suggest a weak El Niño event, but the lack of atmospheric coupling kept the current assessment at ENSO-neutral. On Dec. 10, the Japan Meteorological Agency declared that an El Niño started in late summer and that it would continue through early 2015. This was based on favorable El Niño conditions and elevated SSTs, even while other more robust criteria were not yet met. On Dec. 16, the Australian Government’s Bureau of Meteorology maintained its El Niño tracker status at El Niño Alert status, despite a lack of atmospheric conditions to complement the anomalous SSTs. That outlook assigned a 70 percent probability of a weak El Niño event developing in winter 2014–2015. The Dec. 18 International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) and CPC upped the probability of El Niño conditions developing to more than 80 percent in the next three months and more than 70 percent through spring and into summer (Fig. 3). The North American multi-model ensemble shows a weak event that extends well into spring (Fig. 4). The extended period of above-average SSTs appears to be increasing confidence in the formation of El Niño this winter into spring.

Seasonal precipitation forecasts still indicate an enhanced chance of above-average precipitation over the upcoming winter, but confidence in this forecast is partially contingent on the strength of the emerging El Niño event. The impacts associated with weak El Niño events are generally less certain than those of a moderate or strong event, with past weak events bringing both dry and wet conditions to the Southwest U.S. during the winter. Ultimately, the above-average tropical storm season and the humidity that has remained in the region may be indicative of the effect of El Niño-like conditions, and we may be seeing the emergent effects of El Niño impacts on the climate of the Southwest, despite the absence of a formal definition identifying the start of a bounded El Niño event.